Skin is a living organ and undergoes significant changes during a person’s lifetime: from the delicate skin of a newborn baby, through the teenage years when some are acne-prone, to the wrinkles of later life. Each stage has its own demands and skin care should reflect these changing needs. Choosing appropriate products to cleanse, protect, nourish and repair skin at each of these stages will help to keep it healthy and ensure that your skin looks and feels its natural best, whatever your age.

How is skin different at each age and stage?

Baby skin

A baby’s skin is 20% to 30% thinner than a grown-up’s skin1. It has the same number of layers but each layer is considerably thinner, making it especially delicate and sensitive.

The outermost layer of the epidermis (the horny layer) is particularly thin and the cells are less tightly packed than in adult skin. Sweat and sebaceous glands are also less active and so skin’s hydrolipid film is relatively weak. This means that the barrier function is impaired and baby skin is:

- less resistant

- especially sensitive to chemical, physical and microbial influences

- prone to drying out

- more sensitive to UV

Sensitivity to UV is further enhanced by the fact that babies also have low skin pigmentation. Melanocytes (the cells responsible for melanin production) are present, but less active and so babies should be kept out of the sun.

Babies also have more difficulty regulating their body temperature than adults. This is because:

- the surface area of their body is relatively large

- their sweat glands are less active

- their skin circulation is still quite slow to adapt

It is important that adults are mindful of this and monitor and control the temperature of their environment for them.

Read more about baby skin, the conditions that it is prone to and how to care for it in baby and children’s skin.

1 Source: Pediatric Dermatology 27(2):125-31, October 2009.

Children’s skin

By the age of four, skin and its appendages (such as hair, nails and glands) are a little bit more mature. However, children’s skin is still thinner and has less pigmentation than adult skin. Because these self-protection mechanisms are less developed, young skin is particularly sensitive to UV radiation. Read more about baby and children’s skin and about how the sun affects it in how does sun affect babies and children’s skin.

By the age of 12, the structure and function of a child’s skin corresponds to that of an adult.

The teenage years

The hormonal changes of puberty can have dramatic effects on skin – particularly on the face, shoulders, chest and back. Increased sebum production and disturbed corneocyte shedding can lead to skin becoming oily and acne-prone. This usually disappears as the teenager matures although for some, especially women, acne can go on into middle age and beyond.

Late 20s

Genetics, lifestyle and environment will determine the stage at which the epidermis and the dermis start to thin but, from around the age of 25, the first signs of aging may appear, normally in the form of fine lines.

When skin starts to thin, its barrier function and its natural protection against UV also gradually reduce.

Collagen mass and flexibility also begin to deplete at a rate of approximately 1% a year.

During your 30s

- Skin’s barrier function weakens

- The metabolic processes of the cells begin to slow down

- Skin moisture loss increases as skin produces less Hyaluronic Acid and existing Hyaluronic Acid starts to degrade.

- Collagen continues to degrade at 1% a year and more fine lines and wrinkles form

40s to late 50s

Over the next few decades skin structure gradually changes:

Epidermis:

The ordered arrangement of the individual layers of the epidermis is lost. Fewer cells are formed, existing cells shrink and the top layers of skin become thinner. This can lead to:

- an increase in roughness and dryness

- an increase in fine lines and wrinkles

- areas of hyperpigmentation (known as age spots)

- impaired wound healing and an increased risk of skin infection

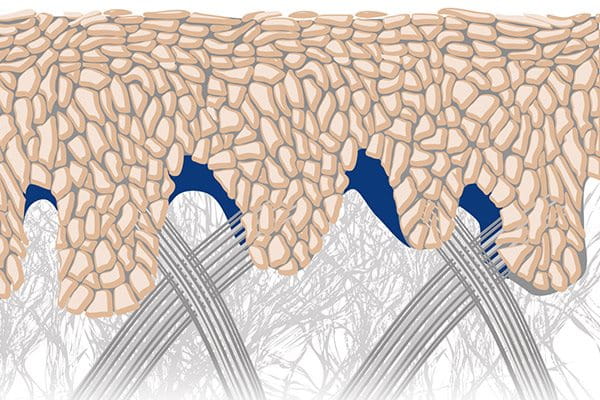

Dermis:

Connective tissues in the middle layer of skin lose their fibrous structure and water-binding ability and start to degenerate. This leads to:

- a loss of volume and a noticeable change in the contours of facial skin

- the development of deep wrinkles

There is also a gradual decrease in micro-circulation in the dermis. The dermis provides nutrients to the epidermis so, without nourishment, both layers and the connections between them become thinner and flatter, resulting in the loss of elasticity common in post-menopausal women. Reduced blood flow also causes a loss of radiance. Skin can appear duller and some broken capillaries may appear.

Subcutis:

The lower layer of fatty tissue gradually reduces, which also contributes to the loss of volume that can lead to deep wrinkles. Skin energy is also reduced and skin becomes less resilient to pressure.

60s & 70s

During your 60s and 70s:

- The skin’s natural ability to produce lipids decreases which, along with the continued decline in Hyaluronic Acid and collagen production, results in dryness, dehydration and deep wrinkles.

- Skin regeneration slows down and it becomes increasingly thin resulting in a loss of elasticity. Wound healing is also impaired.

- UV sensitivity increases and skin is prone to hyperpigmentation (e.g. age spots).

From the late 70s onwards, skin’s immune function has reduced, making it more susceptible to infection.

Read more about skin in skin structure and function and about how it ages in how does skin age and how should I care for it? Male and female skin ages differently. To find out more read how male and female skin differs.

What causes skin aging?

Skin aging is caused by a combination of different factors, both internal and external. Understanding the way that internal and external factors affect skin’s structure and function can help to inform skin care choices and prevent premature skin aging.

Internal factors

Our biological age determines structural changes in skin some of which are inevitable and unavoidable:

- A poorer blood supply means that less oxygen and fewer nutrients travel to the skin’s surface which results in a duller tone.

- Lower sebaceous and sweat gland activity, and a reduction in skin’s natural ability to produce Hyaluronic Acid, result in a weakening of the hydrolipid film and can lead to age-induced dryness and increased wrinkles.

- Reduced estrogen production post-menopause, combined with diminishing cell regeneration, affect the structure of female facial skin by causing a loss of volume and, as skin matures further, a loss of elasticity.

Genetics also play a key role in how skin ages. Our ethnicity, gender and the skin type that we are born with all make a difference to how quickly signs of aging appear on the surface of skin.

External factors

The good news however is that more than 80% of skin aging is caused by external factors which can be influenced2:

- Environmental factors: UV exposure and air pollution.

- Lifestyle factors: smoking, alcohol, nutrition, stress and lack of appropriate skincare.

Read more about the factors that influence skin aging in general skin aging. And find out how to prevent skin from aging prematurely in premature skin aging.

Sun

Research has shown that areas of skin that remain unexposed to sun maintain their tone, elasticity and the ability to regenerate until an advanced age. It is exposure to UV rays that causes photoaging (premature aging caused by the sun). This means that reducing our exposure to the sun and using proven and effective sun protection is a vital step that can be taken to delay the signs of aging. Read more in how do UVA, UVB and HEVIS light affect skin?

Skincare routine

Daily cleansing and skin care using products formulated to match the particular needs of your skin type, condition and age will help to keep skin healthy and delay the signs of premature aging. Read more in a daily skincare routine for the face.

2 Source: ‘Effect of the sun on visible clinical signs of aging in Caucasian skin’ by Frederic Flament, Roland Bazin, Sabine Laquieze, Virginie Rubert, Elisa Simonpietri, and Bertrand Piot, Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013; 6: 221–232. Published online 2013 Sep 27. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S44686 PMCID: PMC3790843

Our brand values

We deliver a holistic dermo-cosmetic approach to protect your skin, keep it healthy and radiant.

For over 100 years, we have dedicated ourselves to researching and innovating in the field of skin science. We believe in creating active ingredients and soothing formulas with high tolerability that work to help you live your life better each day.

We work together with leading dermatologist and pharmacist partners around the world to create innovative and effective skincare products they can trust and recommend.